Do you want to know about the circulation life of a library book? Or what does winter at -37F look like in Yellowstone National Park?

Check out the Top Ten Videos of 2024 from The Kids Should See This

Do you want to know about the circulation life of a library book? Or what does winter at -37F look like in Yellowstone National Park?

Check out the Top Ten Videos of 2024 from The Kids Should See This

Have you ever reached the end of a busy week and wondered, What did I accomplish? If so, you’re not alone. Keeping track of your daily activities, goals, and reflections can feel overwhelming—but it doesn’t have to be. Enter the daily log: more than a planner, it’s a personal record that helps you track what’s coming up and what you’ve achieved and experienced.

Today, we’ll explore the definition of a daily log, why it’s worth your time, and how you can get started with tools and techniques that work for you.

A daily log is a hybrid between a traditional planner and a journal. It’s a place to record your appointments, to-do lists, and goals—but it doesn’t stop there. A good daily log also captures the following:

Unlike a standard planner that looks forward, a daily log also looks back, creating a rich history of your life and productivity.

If you’re still unsure whether a daily log is worth the effort, here are five compelling reasons to give it a try:

A daily log helps you capture what you’ve done—not just what you planned to do. This clearly shows your progress, even on chaotic or unproductive days. For example, noting that you “finalized the Q4 report” or “researched new project ideas” can remind you of the forward momentum you’re making.

Your daily log becomes a personal time capsule. Whether it’s tracking professional milestones, noting personal growth, or capturing special moments, it’s a powerful tool for reflection. A quick flip through old entries can reveal how far you’ve come.

By regularly logging your days, you may notice patterns in your habits, energy levels, or productivity. For instance, you might find that you’re most focused in the morning or that certain tasks drain your energy.

A daily log isn’t just for work. It’s also a way to recognize small victories, like completing a challenging workout, having a meaningful conversation, or enjoying a favorite meal.

Taking a few minutes daily to log your thoughts and activities helps you process your experiences. This practice promotes mindfulness and can reduce stress by clearing mental clutter.

Ready to start logging? Here’s how to create a system that works for you.

Decide whether you prefer an analog or digital format. Each has its pros and cons:

Here are some ideas to structure your entries:

Don’t overcomplicate it! A daily log should be functional, not perfect. Aim for consistency rather than perfection.

Tie your logging practice to your morning coffee or bedtime wind-down routine. Even spending five minutes a day can make a difference.

A daily log is more than just an organizational tool—it’s a way to capture your life story. By tracking your progress, celebrating your wins, and reflecting on your experiences, you’ll boost productivity and gain clarity and mindfulness.

The Eclectic Educator is a free resource for everyone passionate about education and creativity. If you enjoy the content and want to support the newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps keep the insights and inspiration coming!

I’ve talked about building a personal library in the past, and trust me; I am still diligently working on building my own (much to my budget and wall space concerns).

But, I went down a bunny trail on “foundational texts” that people deem important to their thinking and way of life.

It took me a bit and with a little more thinking time, I’d probably change or add more to this list.

How about you? What texts do you consider “foundational” for your life?

The Eclectic Educator is a free resource for everyone passionate about education and creativity. If you enjoy the content and want to support the newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps keep the insights and inspiration coming!

I know, you’re probably thinking the same thing I was. How do you print a book on DNA? What does that even mean?

Asimov Press’ latest anthology features nine essays and three works of science fiction. Embracing the book’s technology theme, we did something very special: With the help of three companies — CATALOG, Imagene, and Plasmidsaurus — we’ve encoded a complete copy of the book into DNA, thus merging bits with atoms.

This is the first commercially-available book to be written in DNA and sold in both mediums; as physical books and nucleic acids. We are deeply grateful to those who helped make it possible.

Also, this process has been done before. George Church at Harvard published his 2012 book Regenesis with DNA, and a group of Cambridge scientists published Shakespeare’s complete sonnets.

I don’t know if this is the coolest or creepiest thing I’ve ever heard about, but I want to know more.

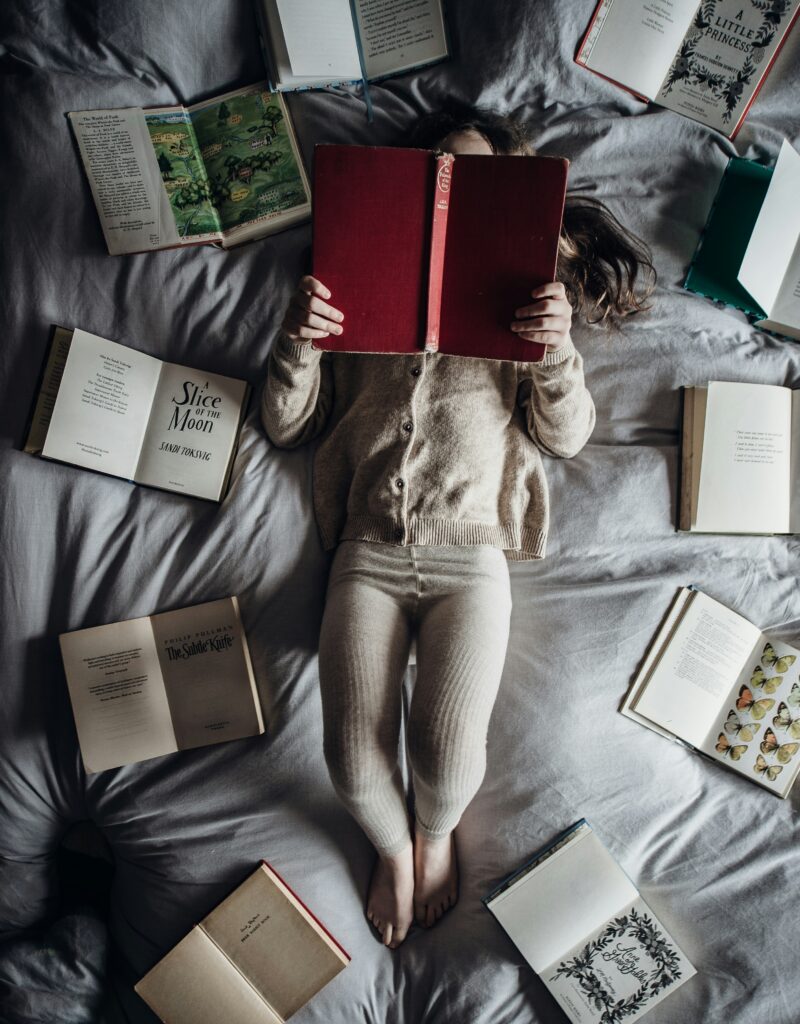

In his thought-provoking video, Jared Henderson delves into why fewer people are reading books, citing issues with education systems, distractions from technology, and a lack of reading stamina. As an educator and avid reader, I agree with what Henderson outlines. However, I also see opportunities to expand on his points and explore some counterarguments.

Henderson highlights the shift from phonics to whole language learning as a pivotal moment in literacy education. He’s right—whole language learning left many students unprepared to effectively decode and engage with text. With its structured approach to sound and word recognition, Phonics builds a foundation that whole language approaches often neglect.

Yet, the story isn’t so simple. Literacy rates are influenced by more than just methodology; systemic issues like underfunded schools, inequitable access to resources, and cultural attitudes toward reading also play significant roles. Blaming the whole language strategy alone risks oversimplifying a complex problem. The good news is that the pendulum is swinging back toward phonics-based instruction in many places, but we must also address these broader systemic issues.

Henderson’s point about reading stamina is crucial. Students trained to extract information from short texts for standardized tests are ill-equipped to handle dense, long-form reading. I’ve seen this firsthand in my work with high school and college students. Reading stamina, like physical stamina, requires regular practice and gradual increases in difficulty.

However, there’s a counterpoint worth considering: is the problem stamina or engagement? Many students might struggle to read long texts simply because they find them irrelevant or boring. To rebuild a culture of reading, educators must consider how to make books feel meaningful in a world full of competing distractions. The classics are essential, but so are diverse, contemporary texts that reflect students’ lived experiences.

Henderson is spot-on when he identifies technology as a culprit in the decline of book reading. With their endless notifications and instant gratification, smartphones make reading a book seem like climbing a mountain when a treadmill is right next to you.

Yet banning phones in classrooms, while helpful, doesn’t address the root of the issue. We must teach students how to coexist with technology, fostering mindfulness and intentionality. Schools could integrate “digital detox” practices, but the more significant cultural shift toward valuing deep focus and reflection must also happen outside the classroom.

While Henderson focuses on literacy and attention, another factor deserves mention: the changing role of books in the digital age. Many young people engage deeply with stories through mediums like podcasts, audiobooks, graphic novels, and even video games. While these formats differ from traditional books, they foster imagination, critical thinking, and empathy. Perhaps the question isn’t why people aren’t reading books but why our definition of “reading” hasn’t evolved.

The path forward is multifaceted:

Henderson’s video lays a strong foundation for understanding why fewer people read books. Still, the solutions require a collective effort. Education, culture, and technology must work together to prioritize deep, meaningful engagement with the text.

Reading may seem like a dying art, but it’s not beyond revival. We just need to adapt to the world while remembering the timeless power of a good book.

The Eclectic Educator is a free resource for everyone passionate about education and creativity. If you enjoy the content and want to support the newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps keep the insights and inspiration coming!