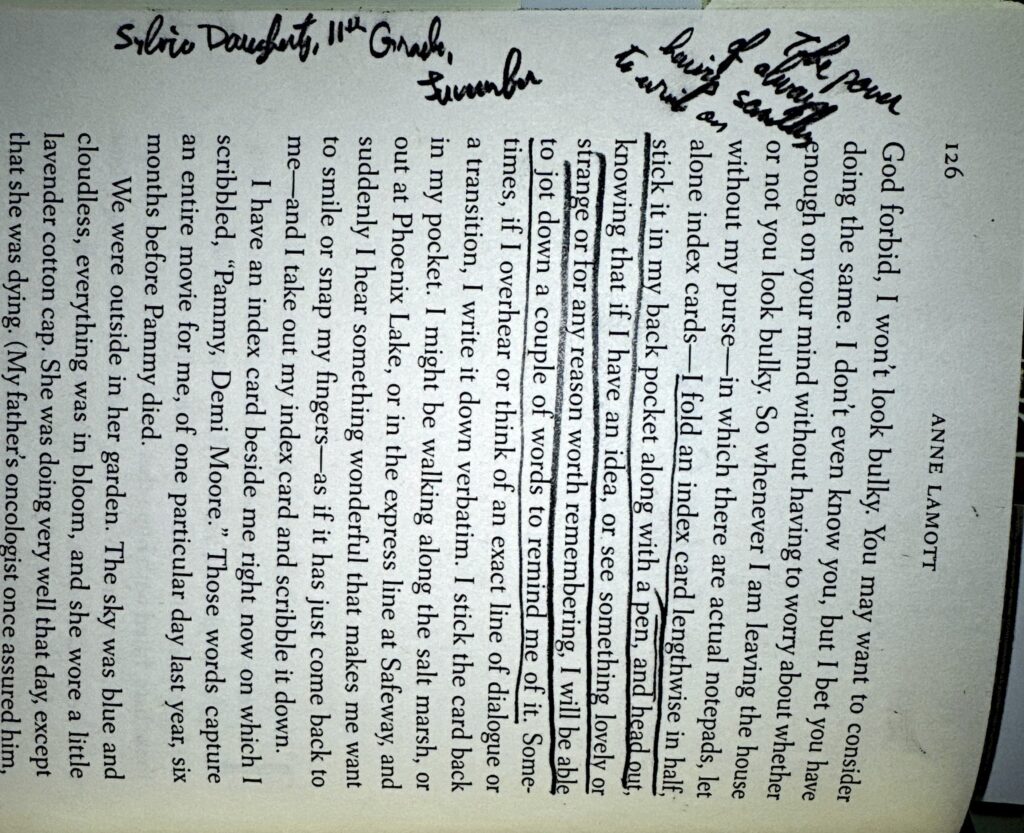

Because I believe each of us is responsible for sharing our learning with the world, I’m sharing a bit of my work.

As my prospectus meeting approaches in a couple of weeks, I’m racing through revisions to my work. I know it won’t be perfect, but I still have a lot I want to complete before that meeting.

Why? Because writing can constantly be improved.

So, a big chunk of the introduction to my dissertation is presented here with little comment unless you know something about my research. At least, this is where it sits right now.

Introduction

The idea of distance learning, the forerunner of online or virtual learning, is not new and has been a topic of exploration for a significant portion of human history. Members of Plato’s Academy used the technology of writing to study Socrates’s great conversations from a distance (Nagy, 2020). Caleb Phillips launched the first shorthand correspondence course by mail in 1728 (Tulane University, n.d.). In the 1890s, the company that would become known as the International Correspondence School (ICS) and later Penn Foster was launched. Within a decade, there were some 250,000 students enrolled worldwide (Buesch, 2020). In 1932, the University of Iowa broadcast programming on the first educational television station and received mail from viewers as far as 500 miles away (University of Iowa, 2022).

Of course, the world of science fiction is no stranger to the idea of distance or virtual learning, as Isaac Asimov, in his 1951 short story, “The Fun They Had,” saw students learning from mechanical teachers (1974) while the children of Ray Bradbury’s seminal “Fahrenheit 451” learned through interactive screens since books were no longer legal (1953). Andrew “Ender” Wiggins spent much of his education in an immersive virtual learning environment, including hours of military simulations disguised as games (Card, 1985). In the far-flung space of the 24th century, crew members, students, and their families aboard the USS Enterprise NCC 1701-D join essentially any time or place and experience events directly in a fully immersive virtual environment through the ship’s Holodeck (Fontana & Roddenberry, Allen, 1987). The virtual learning world even attracts those beyond their schooling years who want to escape their ordinary lives, much like the earthly society depicted in “Ready Player One,” as millions live their lives inside the OASIS (Cline, 2015).

But here in the real world, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a rapid and unprecedented expansion of virtual academies within public schools in the United States. This urgent shift to virtual learning responded to the imperative of continuing education while ensuring safety. The pandemic forced a sudden transition to online education in spring 2020, initially as an emergency measure (Black et al., 2021). This shift introduced many students and educators to virtual learning, previously available to a small percentage of the student population. Before the pandemic, only 3% of school districts in the United States operated virtual schools. This number grew ninefold by the 2021-2022 school year (Diliberti & Schwartz, 2021). While the COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant growth in virtual academy offerings, it also destabilized many of the foundations of public education, creating an urgent need for rethinking public schooling (Ladson-Billings, 2021).

Many school leaders agree that teaching students skills for repetition, recognition, memorization, or any skills related to collecting, storing, and retrieving information are in decline, giving rise to a set of contemporary skills that includes creativity, curiosity, critical thinking, collaboration, communication, growth mindset, global competence, and a host of other skills (Zhao & Watterston, 2021). These skills fall within the overarching concept of deeper learning, a set of competencies students must master to develop a keen understanding of academic content and apply their knowledge to the classroom and 21st-century job problems (William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, 2013). The science of how children learn, grow, and master complex skills has made significant strides in recent years, supporting the ideals of deeper learning. One of the critical components of the science of learning and development is creating learning environments filled with safety and belonging (Learning Policy Institute, n.d.), whether the environment be in-person or virtual. This knowledge is essential for the education of all children, but it has particular strength in achieving educational equity in areas where we have previously fallen short.

References

Asimov, I. (1974). The best of Isaac Asimov (1. ed). Doubleday & Company.

Black, E., Ferdig, R., & Thompson, L. A. (2021). K-12 virtual schooling, COVID-19, and student success. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(2), 119. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3800

Bradbury, R. (1953). Fahrenheit 451. Ballantine Books.

Buesch, K. (2020, October 6). New exhibit: 1920s distance learning. Clarke Historical Museum. http://www.clarkemuseum.org/12/post/2020/10/new-exhibit-1920s-distance-learning.html

Card, O. S. (1985). Ender’s game. Tor Books.

Cline, E. (2015). Ready player one (First mass market edition). BDWY Broadway Books.

Diliberti, M., & Schwartz, H. L. (2021). The rise of virtual schools: Selected findings from the third American school district panel survey. RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA956-5

Fontana, D. C., & Roddenberry, G. (Writers), & Allen, C. (Director). (1987, September 28). Star Trek: The Next Generation [Broadcast]. In Encounter at Farpoint. Syndicated.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). I’m here for the hard re-set: Post-pandemic pedagogy to preserve our culture. Equity & Excellence in Education, 54(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2020.1863883

Learning Policy Institute. (n.d.). Science of learning and development. Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved March 13, 2024, from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/topic/science-learning-and-development

Nagy, G. (2020, March 26). The idea of immediate learning in an age of necessitated distance education. Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/the-idea-of-immediate-learning-in-an-age-of-necessitated-distance-education/

Tulane University. (n.d.). The evolution of distance learning. Retrieved September 20, 2024, from https://sopa.tulane.edu/blog/evolution-distance-learning

University of Iowa. (2022). Milestones in University of Iowa history. https://175.uiowa.edu/milestones-university-iowa-history

William & Flora Hewlett Foundation. (2013, April 23). Deeper learning defined. https://hewlett.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Deeper_Learning_Defined__April_2013.pdf

Zhao, Y., & Watterston, J. (2021). The changes we need: Education post-COVID-19. Journal of Educational Change, 22(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09417-3

The Eclectic Educator is a free resource for everyone passionate about education and creativity. If you enjoy the content and want to support the newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps keep the insights and inspiration coming!