“If a child memorizes ten words, the child can read only ten words, but if a child learns the sounds of ten letters, the child will be able to read 350 three sound words, 4320 four sound words and 21,650 five sound words.”

Dr. Martin Kozloff

Although I’m an avid reader, I’m not a reading teacher. I’ve never claimed to be, and I don’t think I’d do a great job with it. Reading came easy to me at a very young age and I don’t have a clue how to share that magic with anyone, unless I tell them “read”–which is, of course, silly.

If students could start reading on demand, they would, if only to get us to shut up and leave them alone.

Thankfully, more schools across the US have begun implementing programs based on the science of reading to get more kids reading at “grade level.” Yes, I’m fully aware that reading at a grade level is an arbitrary designation, but it’s what we have to work with, and it works.

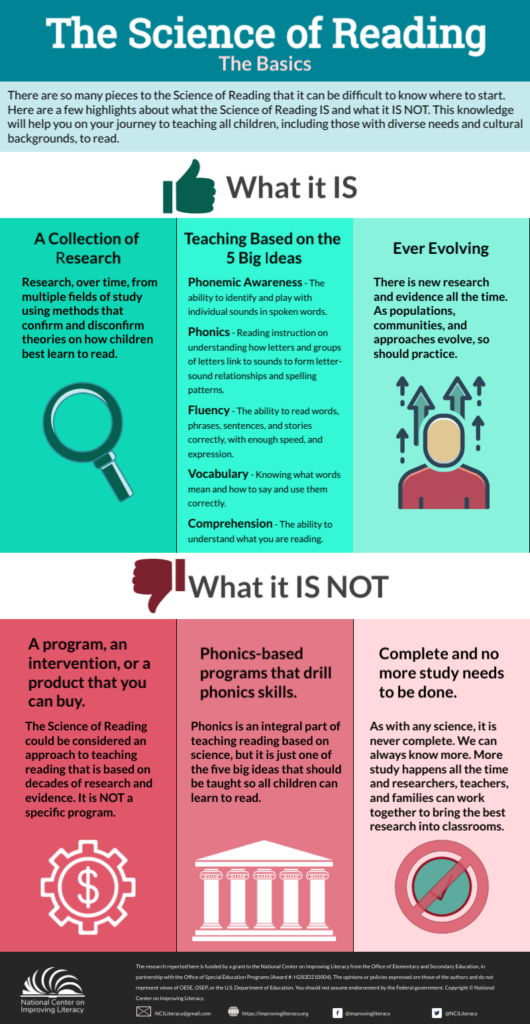

What is the science of reading? Briefly, the science of reading refers to a comprehensive body of research from various disciplines, including cognitive science, neuroscience, and psychology, that explores how we learn to read. This research emphasizes the importance of explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension strategies. It advocates for evidence-based teaching methods that have been proven effective in helping all students learn to read, particularly emphasizing the systematic teaching of reading at the early stages of education.

One curriculum becoming more popular every year is the Core Knowledge Language Arts (CKLA) program. The Aldine Independent District in Texas adopted Amplify CKLA to improve students’ reading proficiency. The curriculum provides students with knowledge-rich, grade-level texts, which helps build vocabulary and a base of common knowledge that fosters inclusive learning communities.

The district has also implemented robust curriculum-based professional learning to ensure teachers are equipped to deliver strong instruction that meets the needs of all students. The program has already shown promising results, with 50% of third graders reading at or above grade level within the first two years of implementation.

Similarly, the Spencer Community School District in Iowa shifted to CKLA for grades K-2 to increase literacy, with great results thus far.

In both cases, the district is focused not just on a new curriculum but also on providing quality professional development for teachers. No matter how great the curriculum is, it can’t work without teachers ready to implement it.

Perhaps more importantly, focusing on changing the hearts and minds of teachers to see how reading instruction was not working in the past and the need for change. In An Uncommon Theory of School Change, the authors posit that before transformative change can take place in a school, we must take a deep dive into the shared assumptions of teachers and wrestle with the fact that what we’ve done before must not be working, no matter how comfortable we are in that teaching.

Bottom line: whatever is best for kids, we need to do that.

The Eclectic Educator is a free resource for everyone passionate about education and creativity. If you enjoy the content and want to support the newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps keep the insights and inspiration coming!